Malta's relationship with Libya

- Spunt Malta

- Aug 22, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 24, 2025

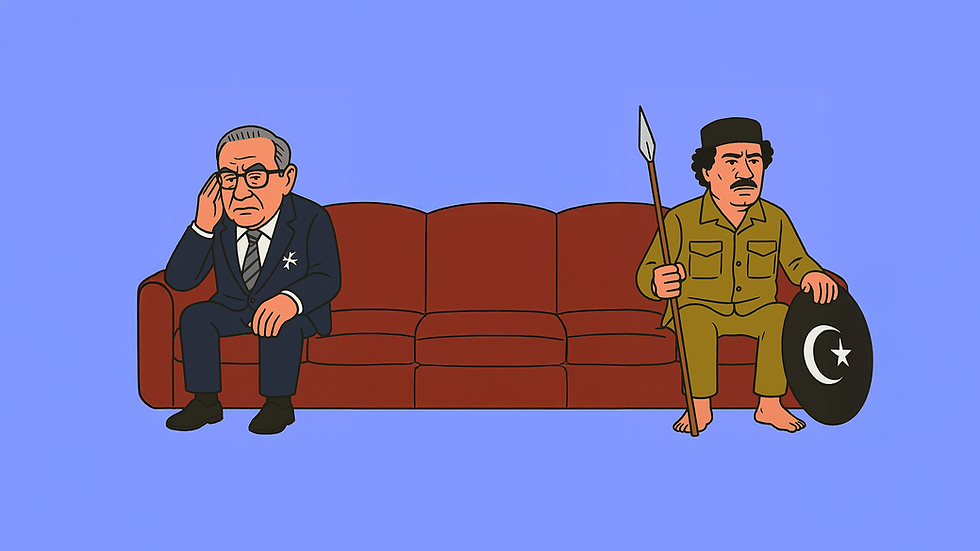

We often forget it, but the closest capital city to Valletta is not Rome, not Tunis, not even Athens. It’s Tripoli. Barely 355 miles to the south, the geographical proximity to Libya has forced a complicated relationship between Malta and Libya. A relationship of friendship, money, politics, suspicion, and at times outright hostility. Libya as a neighbour has always been influential in Malta’s culture and politics, both directly and indirectly, but never has this been truer than in the mid to late 90s.

Seeking legitimacy on the world stage

The year is 1969. Malta is still negotiating its future with Britain, uncertain of what economic independence will look like. To the south, a young officer named Muammar al-Gaddafi leads a coup d’état that topples King Idris, replacing Libya’s pro-Western monarchy with a revolutionary republic.

Malta was quick to recognise the new regime. This was no small thing. Gaddafi was an unknown figure, shunned by many Western governments and Malta’s recognition gave the Libyan leader an ounce of diplomatic legitimacy in the Mediterranean. The parallel struggles were evident. Malta trying to reduce its reliance on Britain, Libya rejecting Western domination both needed each other and this context created a foundation for a friendship that would reshape Malta’s politics and economy for decades.

A “Third Way” for the Mediterranean

At the time, the Cold War created a world of two giants: Washington and Moscow. Gaddafi tried to chart a “third way”, a Mediterranean free of both superpowers. Malta fitted neatly into this vision. For Dom Mintoff, Libya was more than a neighbour. It was leverage. Mintoff often threatened to pivot Malta closer to Libya whenever the Northern neighbours were slow to answer his calls. The friendship gave Malta a bargaining chip with the West, while also filling in crucial economic gaps left behind by the British military withdrawal in 1979. This political flexibility was the first step towards Malta's neutrality, enshrined in the Constitution in 1987.

Malta and Libya's trade

The financial ties were real and not just symbolic. Libya’s first major move was a €20 million loan to Malta in 1975, an enormous sum for such a small economy. By the early 1980s, Libyan money had found its way into several Maltese enterprises: Marsa Shipbuilding, which modernised the island’s dockyard facilities; Medelek, an electronics manufacturer; and Mediterranean Power Electric, which handled energy and utilities.

Libya also pledged to double its imports from Malta and promised to meet all of Malta’s oil demand at subsidised prices. For a country with no natural resources of its own, this was a vital lifeline. At its peak, the Libyan partnership revitalized large parts of Malta’s economy. and infrastructure. Mintoff presented this as Malta standing proudly on its own two feet, free from Western patronage.

Beyond Money

The relationship extended into culture, language, and ideology. Malta’s neutrality in the Arab–Israeli conflict mattered deeply to Gaddafi, who positioned himself as a leader of the Arab world. On Freedom Day in 1979, Gaddafi stood alongside Mintoff and promised Malta “unlimited” military support. Libyan officers and military assets soon became more visible on the islands.

At the same time, Malta opened its cultural doors to Libya. Plans took off for a Libyan cultural centre, a mosque, and a bank in Malta. Meanwhile, Arabic language studies were introduced in secondary schools so that Maltese could learn the language and trade with Libya more easily.

Rough Patches

But proximity breeds friction. When Malta granted Texaco oil drilling rights in the seabed south of the island, Libya claimed the area as its own. Libyan gunboats intercepted the SAIPEM II oil rig, forcing Malta to take the dispute to the International Court of Justice.

The political tit-for-tat escalated. Malta shut down the Libyan radio station after its broadcasts turned incendiary against Israel and Egypt. In 1980, a bomb exploded at the Libyan Arab Airlines office in Valletta, and Maltese task force units searched Libyan residences.

Meanwhile, Libya’s reputation abroad sank further. The regime was implicated in numerous terrorist attacks across Europe. When a bomb exploded on a Rome–Athens flight in 1984, killing four passengers, the United States retaliated by bombing Tripoli and Benghazi.

Malta, under Prime Minister Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici, stood firmly against the American action. In a dramatic claim, Bonnici even announced that Maltese radar had detected the incoming US planes and warned Libya in advance, saving Gaddafi’s life.

Lockerbie and Fatih Shaqaqi

The worst shadow fell in 1988. Pan Am Flight 103 exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland. Investigators argued the bomb had originated from the Libyan Arab Airlines office in Luqa, pinning blame on Malta for loose airport controls. Although US investigators later doubted this version, Malta’s reputation suffered. The tiny island became entangled in one of the Cold War’s most infamous tragedies.

Then in 1995, another shock: Palestinian militant Fatih Shaqaqi, leader of the Islamic Jihad Movement, was gunned down outside the Diplomat Hotel in Sliema by Israeli agents. The assassination once again put Malta in the uncomfortable role of Mediterranean stage for regional conflict.

By the time Malta joined the European Union in 2004, the shift was complete. The country had chosen Brussels over Tripoli. The old relationship with Libya, built on loans, oil, and shared rhetoric, was diluted to a mere shadow of what it once was.

Looking Back

Looking back the Malta–Libya story is one of geography shaping destiny. Too close to ignore, too different to fully align, the two neighbours have lived through decades of uneasy intimacy.

At times, Libya was Malta’s lifeline, but in others it became the island’s greatest reputational liability. And whilst today Tripoli is no longer Malta’s political compass, the echoes of the Mintoff–Gaddafi years still linger.

Malta has not severed its ties with its southern neighbour. In many ways the relationship has simply evolved. Today, Malta often serves as a diplomatic bridge between Europe and the countries of North Africa and the Middle East. Trade with Libya remains significant, and cooperation continues through various security agreements. When Libya was struck by devastating floods in 2023, Malta was among the first to send humanitarian assistance, a reminder that geography still binds the two nations together.

The legacy of the past is therefore not one of abandonment but of adjustment. Malta’s European identity now frames its foreign policy, yet its southern neighbour remains too close, too important, and too entangled in history to ever be ignored.

Comments