The Language Question: Malta’s struggle between Italian, English, and Maltese

- Spunt Malta

- Sep 4, 2025

- 6 min read

The language question in Malta was never a narrow dispute about grammar or schooling. It was a contest over dignity and power, tradition and state authority, and the meaning of Maltese identity under colonial rule. Between the late nineteenth century and the eve of the Second World War, language policy became the central arena in which Malta’s elites, parties, and communities fought over whether Malta belonged to a Latin cultural sphere, a British imperial system, or to a distinct nation with its own voice. The positions were not static. They shifted as political realities changed, yet the underlying psychological tension that Oliver Friggieri described remained constant. Language was a full way of life, not a neutral instrument.

Italian as Malta’s historic language of culture

For centuries, the Maltese "intelligentsia" wrote, legislated, and argued in Italian. This was not an act of disloyalty to Malta. As Friggieri notes, the island’s size and its position in the central Mediterranean bound elites into an Italo-Maltese world that was culturally Latin and regionally oriented, yet locally grounded. To write in Italian was to speak as a Maltese intellectual with recognised forms and vocabulary, and to place Malta within a civilisational continuum that transcended the island’s borders. A Maltese literature existed in Italian because it was produced by Maltese authors for Maltese arguments, even when the medium was Italian.

Maltese itself, though deeply embedded in popular speech, lacked in the nineteenth century a normalised orthography, a settled lexicon for high culture, and an established written tradition. The paradox was sharp. The people spoke Maltese, while the law courts, schools, and literary salons operated largely in Italian. Reformers who prized Maltese as an inheritance struggled against practical limits. Mikiel Anton Vassalli admired Maltese as a “celebre et pretiosum venerandae antiquitatis monumentum” in 1791, yet he wrote his reformist scholarship mostly in Italian because only that medium could reliably carry his arguments to educated audiences. The leading figures who later championed Maltese, including Ġużè Muscat Azzopardi, Dun Karm, Manwel Dimech, and Ninu Cremona, also wrote extensively in Italian before Maltese gained standard form and status. This was a structural constraint rather than an inconsistency.

The British challenge and the 1878 turn

British rule after 1800 introduced English into administration and education. Many Maltese viewed this not as simple bilingual enrichment but as a lever of rule. By the 1870s the language balance reached a critical point. The Keenan Commission of 1878, appointed to examine Maltese education, urged a reorientation toward English throughout the school system. In parallel, Penrose Julyan’s advice framed Italian as ornamental rather than functional. Maltese leaders objected. They warned that English would divide workers who had access to it from those who did not. They insisted that Italian in Malta was not a mere social polish but the living record of a civilisation that justified Malta’s constitutional claims.

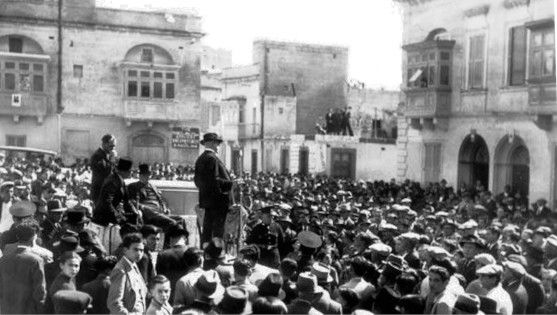

The debate quickly left seminar rooms and entered party politics. Sigismondo Savona’s Reform Party, founded in 1879, backed the anglicising turn. Fortunato Mizzi formed the Partito Anti-Riformista in 1880, later the Partito Nazionale, to defend Italian as Malta’s language of culture and law. “Reform” became a loaded term. In the eyes of Nationalists it meant renouncing the island’s historic patrimony. In the eyes of Reformists it meant modernising education and aligning Malta with imperial opportunity. Both sides claimed to be progressive. Romanticism’s respect for folk culture and popular rights furnished Nationalists with a language of resistance. The British administration framed its policy as rational improvement.

Identity, dignity, and the press

Language was now openly linked to national dignity. The writers’ paper Il-Ħabib, closely associated with Muscat Azzopardi and a circle that included Ninu Cremona, Dun Karm, and others, professed reluctance to engage in partisan politics. The editorial line was cultural uplift in Maltese, not electoral combat. Yet by 1912 the paper made the stakes explicit. “The language which makes of us a separate people, which proclaims us as a civilised people to the world, which reminds Europe that we are a Latin people, is the Italian language. Without it England will see us like the Indians and like those colonies which do not have a history as we have.” The claim was provocative. It did not disparage Maltese. It asserted that Italian signalled Malta’s belonging to a storied European tradition and, by implication, underwrote constitutional aspirations.

British officials, including Gerald Strickland as Chief Secretary and later as Prime Minister, experimented with parental choice of language in schooling and with mixed administrative arrangements. The surface language of compromise sat uneasily with forms of pressure. Nationalists accused the government of campaigning for English as the language of advancement. Imperial rhetoric promised work prospects across the Empire for those who chose English. Italian governments watched closely, and high-level diplomacy sometimes restrained British zeal for fear of alienating Italy. Malta was pulled between cultural gravity toward Italy and the administrative pull of British rule.

The psychological dimension of bilingualism

Friggieri’s central insight is that the Maltese language question was psychological as much as institutional. To force a language upon a community is to reshape daily life, social cues, and the horizon of aspiration. Latin and English patterns of behaviour differed, and the contest between them played out in schools, courts, parishes, and workplaces. The slogan “to force a language upon the people,” used by Fortunato Mizzi and Salvatore Cachia Zammit in 1899, captured this sense of intrusion. Even where bilingualism functioned day to day, it carried unequal prestige. One language spoke of local belonging and family life. Another spoke of office, career, and the imperial centre. The gap between them created a standing tension.

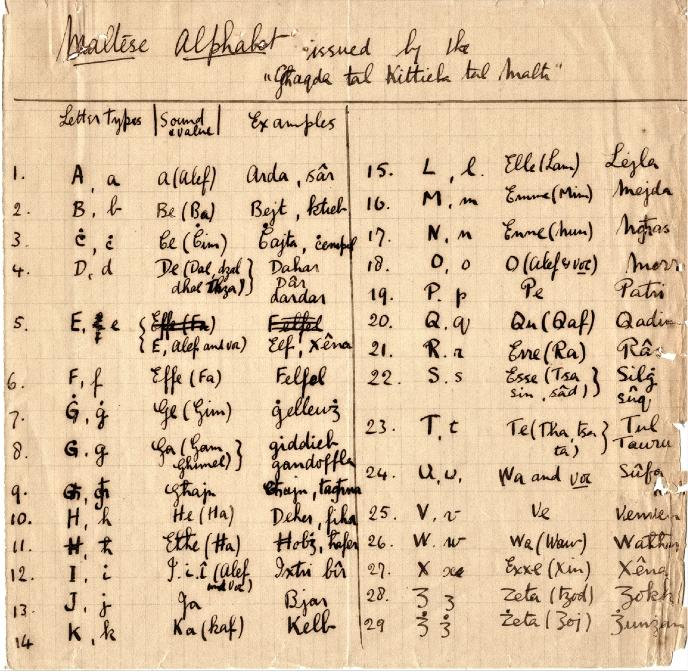

The Maltese language comes of age

From the 1890s onward, the project to raise Maltese into a fully functional written language accelerated. The Akkademja tal-Malti, founded in the early 1920s, standardised orthography and promoted a common alphabet. Maltese literature flourished in poetry, prose, and the press. As technical vocabulary developed, the language moved into courts and public administration. The discovery of Maltese that Friggieri describes was not a sudden switch from Italian. It was a deliberate program that sought to dignify the people’s speech while preserving its historic ties to the wider Latin tradition. The effect was to add a third pole to the debate. Italian represented tradition and Europeanness. English represented imperial power and mobility. Maltese represented a distinct nationhood.

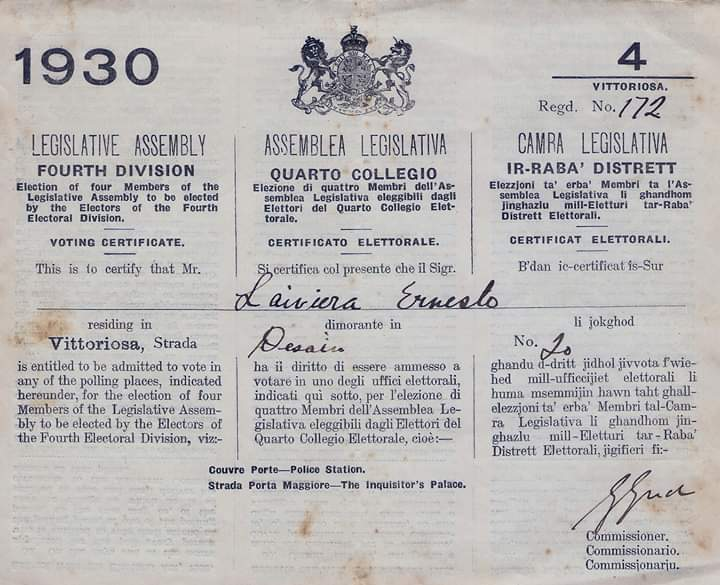

The settlement and its aftermath

By the early 1930s the colonial government had tilted decisively away from Italian. Political crises over education and church-state relations led to repeated constitutional suspensions. Italian influence was increasingly read through the lens of Fascism. During the 1930s Maltese and English consolidated their positions in official life and courts, while Italian lost ground. The Second World War then burned the question into public memory. Italy’s attack on Malta in 1940 made any official role for Italian untenable, even among those who had defended it as cultural patrimony rather than politics. After independence in 1964, the political choice between Britain and Italy was formally behind the country. Yet the frame of mind that Friggieri charts did not simply vanish. Bilingualism continued to encode class, aspiration, and habit. The subconscious affiliations he mapped, between language and entire ways of life, still shape Maltese debates over education, media, and law.

What the language question finally decided

The outcome was not a single victory. English became the language of international business and higher administration in a globalising economy. Maltese gained the status and standardisation that nineteenth-century reformers had only imagined, turning into the primary marker of national identity and a full vehicle for literature, law, and policy. Italian receded from state life, but it left a deep imprint in legal terminology, literary forms, and cultural self-understanding, and it remains an elective affinity for many Maltese who feel the pull of the broader Mediterranean. The language question therefore, resolved into a settlement in which Malta speaks with two official tongues while carrying a Latin memory that still informs style and sensibility.

Friggieri’s analysis helps explain why this settlement feels unfinished. Language policy can be set by ordinance, but the hierarchies and habits attached to languages change slowly. The nineteenth-century debate trained Maltese society to recognise that control over public language is control over the narrative of who counts, which texts matter, and how a people places itself among neighbours. That lesson persisted. It is why the language question remains an enduring reference point whenever Malta considers curriculum reform, court language, media regulation, or cultural funding. The argument began as a clash between dignity and power. It finished as a layered coexistence that still requires care and vigilance, because in Malta language is never just words. It is the country’s chosen way of being in the world.

Sources and notes

Oliver Friggieri, “The Language Question in Malta: The Consciousness of a National Identity,” including quotations on Il-Ħabib and on the dilemma of dignity versus power.

Patrick Keenan, Report on the State of Education in Malta, 1878.

Penrose G. Julyan, correspondence and advice to the Colonial Office on Maltese education and language, 1878–79.

Writings and public interventions by Ġużè Muscat Azzopardi, Dun Karm, Manwel Dimech, and Ninu Cremona on the development of Maltese as a written language.

Akkademja tal-Malti materials on orthography and the standardisation of Maltese in the early twentieth century.

Fortunato Mizzi and Salvatore Cachia Zammit, statements on language and constitutional rights, 1899.

Comments