Swearing and blasphemy in Malta could not be controlled by the Inquisition

- Spunt Malta

- Sep 3, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Sep 4, 2025

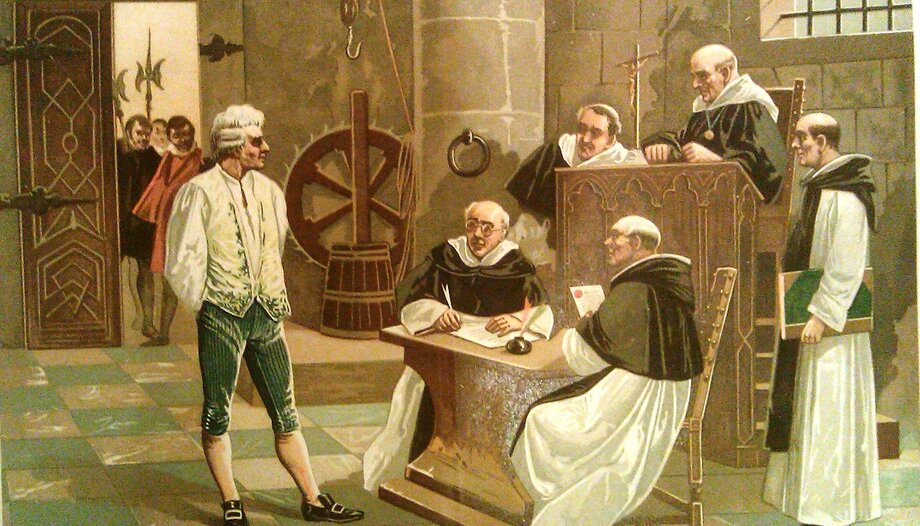

When the Roman Inquisition was established in Malta in 1561, it arrived with extraordinary powers. The Tribunal could summon anyone, question them under oath, and hand down punishments that carried the weight of both Church and Order. Its authority spread into every corner of Maltese life: rooting out heresy, banning dangerous books, policing morality, and dictating what was considered acceptable speech.

And yet, despite all this force, one vice refused to die. Swearing (dagħa in Maltese) proved to be the one habit the Inquisition could never stamp out. The story of how the Malta Inquisition tried, and failed, to silence swearing is both fascinating and almost comic.

The Inquisition and Daily Quarrals

The Inquisition in Malta left behind thousands of pages of records. These were not only about theology but about daily life. They covered arguments, insults, disputes between neighbours, even curses muttered in moments of frustration. Historians today treat them as a window into Maltese culture during the early modern period.

We learn, for example, that Judge Melchior Cagliares once insulted Bishop Gargallo as a vigliacco (coward) in a heated dispute. When later ignored by a friend in the street, Cagliares snapped back in Maltese: “Le tibżax hekkda kif fixkilt l-oħrajn infixkillek” (Loosely translated to: “Do not be afraid, just as you disturbed others, I will disturb you.” ) This insult was not just heard; it was recorded in the Tribunal itself.

In another case from 1582, a woman called Ginaina was injured, and her son was mocked in public. A man sneered at the boy: “Chen ta’ ib min laeta ueei ommok” (“It serves your mother right.” ) The words, petty as they sound, were considered serious enough to enter the records.

These and many episodes show how closely the Inquisition tied itself to everyday life. It was not simply about high religious doctrine. But looked to control words, tempers, and outbursts and other stuff part of any daily Maltese quarrels.

Swearing and the Maltese Inquisition

Anthropologists argue that people usually swear about what they see as most powerful in their lives. For the Maltese, living in a society completely dominated by Catholicism, that meant religion. Their curses were not about random things but about God, the Virgin, or the saints. Ironically, they swore in religious language not because they rejected faith, but because religion was so central to their world that it gave them the strongest words to express anger or frustration.

By the late seventeenth century, with the threat of Protestant heresy long gone, the Inquisition redirected its energy toward another perceived menace: the unstoppable habit of swearing. The Tribunal’s records are filled with cases of Maltese men and women cursing God, the Virgin, the saints, and even holy statues. In 1790, Francesco Pace of Rabat (Gozo) threatened Saint Anthony’s statue, warning, “If you don’t listen to me, I’ll cut off your head and silence you.” Around the same time, Giuseppe Pisano, better known as Ta’ Saram, declared, “If I had caught hold of God, I would have broken Him into pieces under my feet.” Others swore in despair rather than defiance: Evangelista Busuttil, a destitute mother from Xewkija, lamented her miserable inheritance by saying, “So God does not do justice after all.” In Ta’ Sannat, one man mocked the Virgin with the words, “Did the Madonna not fornicate? Then how did she give birth?” To the inquisitors’ frustration, these outbursts were not only frequent but often strikingly inventive. Some Maltese even put their curses into rhyme, leaving behind what reads today like a raw and angry kind of folk poetry.

The Inquisition Strikes Back

The Inquisition tried everything. In 1686, Inquisitor Innico Caracciolo issued an edict against swearing, ordering it to be read in every parish and posted in public squares. Offenders were summoned, fined, or forced into humiliating penances. Some were made to go on pilgrimages; others were warned or shamed before their communities. But the flood never stopped. The Tribunal’s registers filled with case after case, until inquisitors began to despair. Caracciolo himself admitted that the Maltese were so steeped in the vice that “no one was ashamed of it anymore.” Another complained that the number of offenders was so high it was impossible to prosecute them all, and no form of punishment could stop it.

Limits of Power

They could never win the war on swearing because religion itself dominated the language of everyday life. Swearing was also everywhere, functioning more like punctuation than like heresy.. It was not an occasional slip of the tongue but a nationwide habit. If the Tribunal had tried to prosecute every case, it would have ended up putting half of Malta on trial. Overuse also dulled the scandal.

Most importantly, inquisitorial authority had limits. The Inquisition could control books, sermons, and even public rituals, but it could not control every muttered curse of frustration in kitchens, boats, or fields. Language remained beyond its reach, and that is why the battle was ultimately lost.

For the Inquisition, this was a defeat. For historians, it is a gift. The Tribunal’s records preserve the voices of ordinary men and women who would otherwise be silent in history: judges lashing out in anger, mothers lamenting their fate, fishermen threatening statues.

The story of the Malta Inquisition and swearing is not about sin alone. It is about the limits of power, the resilience of popular culture, and the creativity of a people who could not stop speaking their minds, even when their words were scandalous.

Sources Wain Kevin, Blasphemy : a study on power relations between the Roman Inquisition and the common people - https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/90900

Cassar Mario: Nella lingua nostra nativa : l-uzu tal-Malti fil-processi ta' l-inkwizizzjoni Rumana f'Malta - https://bit.ly/4m1zm74

Comments